Microsoft Visual Studio 2012 Torrent Tpb

Picktorrent: visual studio 2012 - Free Search and Download Torrents at search engine. Download Music, TV Shows, Movies, Anime, Software and more.

Servicios Personalizados

- Como citar este artículo

- Citado por SciELO

- Citado por Google

- Similares en SciELO

- Similares en Google

versión On-line ISSN 0718-2724

http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-27242016000300005

Associations for Disruptiveness - The Pirate Bay vs. Spotify

Bjorn Remneland Wikhamn 1*, David Knights2

1 Department of Business Administration, School of Business, Economics and Law, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

2 Department of Organization, Work and Technology, Lancaster University Management School, UK

*Corresponding author: bjom.remneland@handels.gu.se

Abstract: Most studies on disruptive innovations adopt technology-centric assumptions when explaining how industries are affected by a technology's creative destruction. This paper argues that the power of a technology lies in how it performatively associates with the cultural and social norms of the wider society. Hence, a technology is not disruptive or sustaining in itself but is potentially a productive outcome of network linkages with other social and material elements. To illustrate this claim, two digital music services will be analyzed, respectively a misfit and a maverick both challenging mainstream providers of music - The Pirate Bay and Spotify - in relation to each other and how they are positioned toward the transformation of the music industry as a whole.

Keywords: Innovation; disruptive technologies; discontinuous innovation; radical innovation; digitalization; translation; Actor Network Theory; music industry; Spotify; The Pirate Bay

Introduction

The idea of disruptive technologies (Christensen, 1997) has been often highlighted in the management and innovation literature in recent years. Much of this theorizing focuses on the 'incumbents' curse' (Chandy & Tellis, 2000; Foster, 1986) and the difficulties for established firms to align to new technological paradigms (Dosi, 1982). Some have directed attention to how firms can manage radical, discontinuous and disruptive innovations in relation to existing internal knowledge structures and processes (Dewar & Dutton, 1986; Ettlie, Bridges, & O'keefe, 1984; McDermott & O'Connor, 2002). Others (e.g. Rogers, 1962; Utterback, 1994) have looked at how novel innovations form distinct diffusion patterns, where critical masses over time have the ability to weed out old regimes through positive feedback loops. Both these directions take the quasi-deterministic stance where the technology is seen to have an innate capacity to transform society and the focus of these authors is simply to record the processes. From this viewpoint, disruptive power is exerted through the technology's inertial force and the medium's way of transmitting its execution in an effective manner.

This article will highlight an alternative framework to explain disruptive outcomes, arguing in line with actor network theory (Callon, 1986, 2007; Callon & Latour, 1981; Latour, 1986) that the disruptive power of a technology is not found merely in its inner core, but rather in how it performatively associates with the cultural and social norms of the wider society. In this sense we need to focus on the numerous and complex ways that certain notions of technology 'are (or fail to be) articulated and mobilized in diverse - academic, consumer, media as well as practitioner - discourses' (Knights, Noble, Vurdubakis, & Willmott, 2002, p. 113). A technology is not in this framework disruptive or sustaining in itself but just often labelled so (Knights & Vurdubakis, 2005) whereas it is more often a productive outcome of a network of enrolled linkages with other social and material elements (Callon, 2007). This actor network theory (ANT) approach is still comparatively rare in the theoretical analyses of disruptive innovation since generally precedence is given either to the material aspects (i.e. technology) or to the social aspects to explain disruptive outcomes (Orlikowski, 2007). Put differently, the most common approaches to innovation take either a technological determinist view where new technologies are seen to disrupt organizational and social routines or a social shaping approach in which it is the cultural and social interpretations of a technology that are seen as instrumental in creating change (MacKenzie & Wajcman, 1999). ANT breaks down this technical - cultural binary to facilitate a socio-material understanding of the enrolment of material artefacts and actors in the mobilisation of alliances that stimulate and sustain change and innovation.

To illustrate the socio-material link in disruptive innovations, two digital music services will be analyzed - The Pirate Bay and Spotify - in relation to each other and also in how they are positioned toward the transformation of the music industry as a whole. Both ventures could be seen as successfully implemented innovations, with the same Swedish geographical roots and performing similar tasks of distributing music to end-users through the application of new digital technology. But as they have gained acceptance among music consumers, the two initiatives have had a very different reception in relation to the dominant incumbents of the music industry. This facilitates a comparative analysis and a nuanced theoretical reflection on the performance of digital technologies in the music industry, and how 'disruptive' innovations rely on elements beyond their technological core (Knights and Vurdubakis, 2005). Indeed, the way digital media is designed but also organized and associated with various other elements poses radically different challenges and implications for the protection and creative development of the music industry.

According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), global recorded music revenues fell from US$ 25.1 billion in 2002 to US$ 15.0 billion in 2013 (IFPI, 2014). The industry is often portrayed to be in crisis and the main evil is piracy, facilitated through the 'digital revolution' of peer-to-peer file sharing. Digitalization is repeatedly said to strike hard on creative industries, such as music, film, books, and games, as the non-rivalry of digital goods are able to travel without necessarily taking copyright issues into consideration (Benkler, 2006; Lessig, 2004). 'Digitalization' is thus frequently equated with 'radical' and 'disruptive' movements on the market (Bower & Christensen, 1995). Interestingly, though, despite the decline in overall music revenues, sales through digital services have increased to a US$5.9 billion business in 2013, making up for more than a quarter of the recording companies' current revenues (IFPI, 2014). Far too often, digital media is talked about in overly simplistic terms and lumped together as one technology with generalizable consequences, despite the obvious differences among the plenitude of digital media services emerging (Baym, 2010). Most of them can be seen as new and creative, but are they also inevitably disruptive to the incumbents' market positions in the sense that they challenge the oligopolistic corporate structure of the music industry? We seek to contribute to the debate by providing one possible answer to this question.

Method

The article is mainly conceptual, drawing on actor network theory as a lens through which to examine the organization and disorganization of radical innovation (e.g. digital technologies and peer-2-peer) in the music industry. A comparative case study is utilized to illustrate similarities and differences between radical innovations and their association and/or dissociation with industry incumbents and end-users. Case study research is a well-established method to generate new and empirically valid insights (Abbott, 1992; Eisenhardt, 1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Flyvbjerg, 2006; Stake, 2000). Keeping in mind that case studies do not allow for statistical generalisation, they can still provide analytical generalisation in the transformation of empirical data to theory, rather than to a population (Yin, 1994). Cases can provide good illustrations of dynamic processes played out over time (Siggelkow, 2007) and can generate insights about a particular issue or topic (Stake, 2000), such as the disruptive elements of music innovators.

The two cases in this article - Spotify and The Pirate Bay - as well as the industry as a whole, are all appropriate for the purpose of analysing radical and disruptive innovation. This is due to current transformations that are partly driven by technological advancements but also because of the rather intense rhetorical 'war' between the media corporations and the 'pirates'. The Spotify case represents the 'legal' actor, and the Pirate Bay case represents the 'illegal' actor. Over the years, both services have gained strong positions on the global music market and have taken active roles in transforming music consumption at large. The information about the two cases is based on official documentation in books, blogs, news articles, TV interviews, their websites, court material and through other similar references.

The article is structured as follows; in the first section we examine the literature on radical and disruptive technologies where the predominant model is that of diffusion, which we challenge. The second section explores a theoretical framework that focuses on the sociology of translation as developed by actor network theory. We then turn to our comparative analysis of the two innovations in the use of digital technology in the music industry - the Pirate Bay and Spotify.

Discontinuous, radical and disruptive technologies

Technology is often argued to act as a central force in shaping conditions for organizations and societies (e.g. Dosi, 1982; Solow, 1957; Teece, 1986; Tushman & Anderson, 1986). Much in line with Kuhn's (1965) theories of science, Dosi (1982) introduced the ideas of technology paradigms and technology trajectories to explain continuous and discontinuous change. He suggests that technology evolves through certain trajectories based on taken-for-granted paradigmatic assumptions on possibilities and limitations, which occasionally are being disrupted to form new trajectories (ibid.). Of course, technologies such as the instant communications provided by mobile phones can be simultaneously positive in facilitating innovations in production while disrupting its uninterrupted continuity (Rennecker & Godwin, 2005). As technology advancement is path dependent (Coombs & Hull, 1998), firms develop installed bases (Farrell & Saloner, 1985) and dominant designs (Anderson & Tushman, 1990) with high switching costs in both core capabilities and materialized structures. Schumpeter's (1934) notion of creative destruction points to the proposition that the obsolete must be torn down in order for something new to emerge. Technological innovations, thus, always have a relation to the past if only to be a contrast with that which they supersede.

The type, level and effect of a technology's creative destruction have been portrayed in various ways. Tushman and Anderson (1986) suggest that technology change happens through a cumulative, incremental process until it is punctuated by a major advance, what they call a discontinuous innovation. Such major breakthroughs strongly improve the performance or price level in relation to existing technologies and their advancements are so significant that older technologies cannot compete through greater efficiency, design or economies of scale. Another, highly interrelated, way of distinguishing the degree of innovativeness in relation to incremental change is through so called radical innovation. Ettlie, et al. (1984) argue that innovations are radical when they are new to the firm and to the industry, and/or require substantial and costly changes in the firms processes as well as output. Radical innovations have also been coined as breakthrough inventions (Ahuja & Lampert, 2001) or pioneering innovations (Ali, 1994) or highly innovative products (Kleinschmidt & Cooper, 1991) which are all based on substantial technolgoical advances that offer new technological trajectories and paradigms (Dosi, 1982). Chandy and Tellis (1998) classify innovations along two dimensions; newness of technology and degree of customer need fulfilment per dollar, arguing that incremental innovations are low on both dimensions, while radical innovations are high on both. All these ways of defining the extent to which innovations are radical relate to how they divert from established knowledge and practices.

Abernathy and Clark (1985) argue that major technological shifts can have both creative and destructive effects on the existing industry. Innovations can disrupt the market by introducing new knowledge competences and/or relationships but they can also consolidate existing knowledge competences, linkages and market positions. This view is also repeated by Tushman and Anderson (1986) who characterize technological discontinuities as competence-enhancing or competence-destroying, suggesting that the former builds on embodied know-how in the replaced technology while the latter render the knowledge in existing technologies obsolete. Christensen (1997, p. xv) popularized the term disruptive technologies, arguing that they 'bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously'. Disruptive technologies are often characterized as initially underperforming dominant alternatives in the markets along the dimensions that the mainstream customers currently value. However, over time they will displace the dominant technologies because they offer alternative other features, which customers earlier did not want or were unaware of, but eventually will learn to appreciate. Disruptive technologies are also associated with the displacement of market power, where new entrants tend to weed out previously successful incumbents (Chandy & Tellis, 2000). This could be seen as a specific type of technological change, operating through specific mechanisms and having particular consequences (Danneels, 2004). Disruptive technologies can therefore be understood as acting on different dimensions than radical innovations such that, for instance, 'the radicalness is a technology-based dimension of innovations, and the disruptiveness is a market-based dimension' (Govindarajan & Kopalle, 2006, p. 14). In a sense, this moves the continuum further over so that the opposite of disruptive innovation becomes not incremental but sustaining innovation. As Sandstrõm (2011) has shown, these displacements can take place in both low-end and high-end segments.

Danneels (2004) has raised some further critiques of the notion of disruptive technologies. One such is the problem of defining what a disruptive technology really is (e.g. What are the essential characteristics of a disruptive technology?). For instance, Christensen's early work (Christensen, 1997) focuses on the technology aspect of innovation, while his later work (Christensen & Raynor, 2003) brings in a larger variety of innovation types as potentially disruptive for the incumbent firms. Markides (2006) argues for the importance of separate disruptive business model innovations as opposed to technological innovations since they 'pose radically different challenges for established firms and have radically different implications for managers' Markides (2006, p. 19). Danneels (2004) also points to the challenge of knowing at what exact time a technology becomes disruptive, and for the possibility of applying the theory to ex ante predictions. He urges further research to develop analytical tools for identifying (potentially) disruptive technologies - a call which has been accepted by, for instance, Govindarajan and Kopalle (2006).

Actor Network Theory as a framework to analyse disruption

In challenging the mainstream assumptions about disruptive techno-logies, this article raises questions whether it is possible to find the power of disruptiveness in the technology or the innovation itself. As Latour (Latour, 1986, p. 264) argues, 'power is not something one can possess - indeed it must be treated as a consequence rather than as a cause of action'. By this he separates out power in potentia, that is, something you perceive to 'have', and power in actu, i.e. actual power to enforce. The latter is always dependent on the actions of others rather than some intrinsic characteristics of the sender. Latour's argument is a continuation of Foucault's (1980, 1982) ideas that power is not possessed, but exercised, and that action is always action on the actions of others. Translating this discussion to the field of innovation, technologies can only be considered as disruptive if the surrounding elements act accordingly. True, to a large extent innovators try to inscribe the behaviours of the users (Akrich, 1992), but the intended scripts do often meet with anti-programs and descriptions that are unintended (Latour, 1987).

Callon (1991, 1992) explains the link between the 'social', 'technical' and 'economic' by introducing the concept of techno-economic network as 'a coordinated set of heterogeneous actors which interact more or less successfully to develop, produce, distribute and diffuse methods for generating goods and services' (Callon, 1991, p. 133). For him, the dynamic relationships amongst these actors are being held together through the circulation of intermediaries such as money, artefacts, texts and human beings, and the durability and robustness of these associations determine the success or failure of the innovation. Latour (1986) argues in similar ways, that the power of a token (e.g. an innovation) lies in its ability to hold together associations with other material and non-material elements in durable forms. 'It's not technology that is 'socially shaped', but rather techniques that grant extension and durability to social ties' (Latour, 2005, p. 238). Depending on which elements it succeeds in attracting and stabilizing, the innovation transforms activities and relations in different ways (Callon, 1986). In other words, an actor is a network of relations and it is from these relations that the innovation is perceived. In the making of such process, it is therefore not known whether the outcome will be sustaining or disruptive, and which actors or actants it will transform (Latour, 1996). For ANT, then knowledge and innovation is best understood as a hybrid of objects, social artefacts and discourses that are organized through material and non-material agents mobilised for purposes of securing the actor network, despite continual disruptions and processes of reassembly (Latour, 2005). Callon (1986) introduced four moments of translation; 1) problematization in which the actor is defining the nature and problems of stakeholder groups and making itself an 'obligatory passage point' for providing a good solution; 2) interessement, where the network locks the others into different proposed roles by building physical and mental infrastructures which tie the stakeholder groups to the network; 3) enrolment refers to the negotiations, seductions, argumentations and sometimes force to coordinate the emerging network; and 4) mobilization describes relations that have been strengthened in so far as the allies are (at least temporarily) obedient and opponents silenced, providing the initial actor with power in actu.

To illustrate this alternative framework inspired by the sociology of translation and actor network theory, a comparative case study of two digital music services will now be introduced and analysed in relation to the copyright owners and the music consumers. It demonstrates how the often labelled 'disruptive', radical and discontinuous digital technologies related to music production and distribution have had a creative impact on the music industry and its various stakeholders over the years.

Case comparison

Many new digital services have emerged in the last ten years to take advantage of the 'radical' information technologies in the music industry. MP3.com, Napster, KaZaa, Limewire, BearShare, iTunes, Amazon MP3, Myspace, YouTube, Zune, the PirateBay, LastFM, Spotify, MOG, WiMP, Beats Music, Vevo, Pandora, Deezer and Google Play are only a few of the many actors which have gained much public recognition through information-pull rather than information-push technologies (Duchêne & Waelbroeck, 2006). Some of these ventures act in a grey zone of intellectual property rights (or even clearly overriding them), which have made them official enemies of the big recording companies. The user-friendly, cheap and not easily controlled distribution process brings a perceived threat to actors traditionally earning their profits from exploiting copyright material, in the fear that pirate copies will substitute the purchase of the original and thus reduce company profit. But, as (Baym, 2010, p. 17) argues, 'even as we are concerned with their impact, we must avoid the temptation to look at new media only as a whole. Each of these media, as well as the mobile phone, offers unique affordances, or packages ofpotentials and constraints, for communication'. Pirate Bay and Spotify are two different kinds of these digital music services that illustrate similarities but also differences in how digital music services develop their strategic attempts to make a mark in the industry.

The case ofthe Pirate Bay

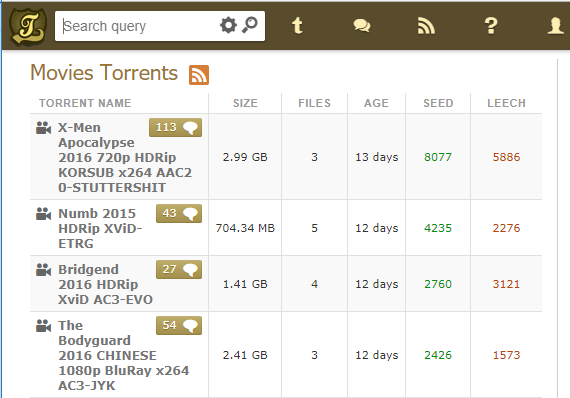

The Pirate Bay (TPB) has been known as an open website for indexing so called torrents, i.e. small protocols including metadata for directing the file sharers to digital content. As such it has functioned as a virtual meeting place for exchange of, among others, music files (MP3 and music videos), and has gained much attention among file-sharers as well as in the news media. TPB has over the years often been argued to be the biggest search tool for torrents, with tens of millions of active users and access to more than four billion torrent files.

The site was first launched in 2003 on a server in Mexico, where the Swedish hacker and one of the alleged founders, Gottfrid Svartholm Warg, was then working. The venture had emerged from loose conversations on an IRC channel between him and Fredrik Neij, with the initial idea to build a tracker for local, Swedish material. As the usage expanded also internationally, more hosting capacity was needed and TPB was moved to bigger servers in Sweden in 2004. Peter Sunde, a friend of Neij, also become involved early on in the project. As the most politically active of the three, he became a public spokesperson for the platform (a post he formally left in August 2009). The people behind TPB have from the start been actively involved in the public debate on file-sharing, arguing for the users' right to copy and spread digitalized culture. The logotype of TPB is a pirate ship with set sails. It carries a modification of the Jolly Roger flag, in which the skull is replaced by a cassette band, as an ironic critique to an anti-copyright infringement campaign from the 80s, 'Home Taping Is Killing Music'. On the website, TPB openly published letters from various actors threatening to take legal action against them. They also publish their own replies, which are written with a mixture of scorn, mockery and humour.

TPB was designed to provide a searchable index of torrents. It was built on a software called open tracker, which is one of several free trackers on the market and they are all designed to be fast and to use minimal system resources. A torrent is a small data file with an address to a specific content and a link to all the other users of the same torrent. These torrents can be downloaded from search engines such as TPB, but to activate the link in order to start the actual uploading and downloading, the user needs to have a certain client software (there are many free so called BitTorrent clients on the market). Through this program, the torrent locates other active torrents, to start the file-sharing. A group of users which have activated the same torrent is known as a 'swarm'. As one user begins to download the file, other active users in the swarm can start downloading the finished content from him or her. This makes it a fast and resilient process even for large data files, since it distributes the load to many users. In fact, contrary to when a file is accessible from only one location, this peer-to-peer technology makes the process faster the more users are taking part.

TPB was not designed to allow much social interaction between users, above the actual peer-to-peer sharing of digital content. Possibilities were created for the uploader of the torrent to add information about its content (type, number of files, size, tags, quality, name of songs, artists etc.) to other users, and for other users to give comments on the content and do ratings on its quality. However, very few social cues about the anonymous users were embedded in the system. Members could create individual profiles based on their user names, but this profile only discloses the level of activity in terms of the number of uploads. While limited in the variety of social cues, the profiles provide the opportunity for active users to build a reputation in relation to quantity, quality and newness of their uploaded material. The imputed tag information in the torrents together with the aggregated ratings and possible content comments, may also affect the propensity for new users to download a particular file.

Visual Studio Version 2012 Download

In terms of storage, early on TPB decentralized the location of the actual digitalized content to the participating users' own hard drives. This gives at least three advantages; it reduces the risk of legal threats toward the service (although TPB did face a trial and prosecution in 2009), it makes the peer-to-peer technique more effective, and it provide users total offline access to the material. The fact that the content is downloaded as digital files of standardized formats, it spurs the mobility of the content. Users can easily replicate or convert the files and spread them further - to other users as well as to other types of devices. TPB has been positioned as 'the world's most resilient BitTorrent site' and as such it has a considerable reach, but it does not in any way prohibit or compete with other similar web services. Rather the opposite.

On 31 May 2006, the police made a big raid against TPB, confiscating all its servers. A preliminary investigation was conducted which on January 21 2008 led to Swedish prosecutors filing charges against Neij, Svartholm and Sunde together with the businessman Carl Lundstrõm who owned the company Rix Telecom where TPB servers were hosted in Sweden. All of them were charged with 'promoting other peoples infringements of copyright laws'. In April 2009, they were found guilty to accessory to crime against copyright law by the district court and sentenced to one year in jail each, as well as fines of approximately $3,5 million (30 million SEK) paid to a number of music-, movie- and game corporations. The lawyers of all four defendants appealed the verdict. On 26 November 2010, a Swedish appeals court returned the verdict, decreasing the original prison terms (Neij to 10 months, Sunde to 8 months and Lundstrõm to 4 months) but increasing the fine to 46 million SEK.

The legal process did, however, not totally shut down the website, despite the fact that those initially involved at least officially left the project. Several further setbacks have however occurred since. Following a complaint from the British Phonographic Industry (BPI), on 30th of April 2012 the High Court in London issued a ruling that six major internet service providers in the UK should block their customers from using TPB site. Similar rulings have since then been taken in numerous other countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Italy. Also web services such as Facebook and Microsoft Live Messenger have censored links to the Pirate Bay site. In August 2013, TPB announced the release of a free web browser which enables users to sidestep this type of 'censorship', and there are also numerous other simple ways to circumvent the block that are readily communicated through social networks. In December 2014, the Swedish police raided a web server location in Stockholm which made the TPB site go down. In a few days, several new alternative sites emerged, mirroring the old version of TPB. These forms of hostile actions from the legal system pose a great threat to websites such as TPB, and these actions mainly lead the 'pirates' to start looking for other, more effective alternatives. So despite a loss in the court leading to the closure of the TPB service, there have emerged new innovations and organizing mechanisms, or the enrolment of other actors that have developed less traceable interactions or other ways of commercializing the service. A few months later, the Pirate Bay opened again.

The case of Spotify

Spotify is a music streaming service founded in 2006 by the Swedish entrepreneurs' Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon. As summarized on Spotify's homepage in 2010;

Spotify is a new way to listen to music: Any track you like, any time you like. Just search for it in Spotify, then play it. Any artist, any album, any genre - all available instantly. With Spotify, there are no limits to the amount of music you can listen to. Just help yourself to whatever you want, whenever you want it. (2010-10-07)

The service was initially run as a beta version in a smaller invitation-based community until it was officially launched in October 2008. By signing licensing agreements with all the major record label companies, as well as a multitude of independent labels, Spotify positioned itself as a music provider, in contrast to 'piracy' alternatives. From the start the service was available in Sweden, Norway, Finland, Germany, Italy, France, the UK and Spain, but it rather quickly spread to other countries. Starting as a small venture, it has been established as a company with 200 employees and headquarters in the UK. In September 2010 Spotify had a big party in London, celebrating their outreach to10 million users across Europe. At that time, it offered access to a catalogue of more than 10 million tracks. In July 2011, Spotify launched its US service after years of negotiation with the major record companies. In December 2012 the service reached 20 million users with 5 million subscribers, and in January 2015 it had reached 60 million users with 15 million subscribers.

The service is based on a free but proprietary client program which the user needs to download and install, and is therefore not a pure web-based service. From the application, the user can search and play music and also put together own playlists for easy access. Spotify was initially built on a combination of server-based streaming and peer-to-peer technology where users transferred music in peer-to-peer fashion similar to the torrent technology. This technique allowed Spotify to reduce the huge costs for server resources as a startup, but as of the fall 2014, Spotify only stream from own servers. The fact that Spotify uses streaming technology where the music is not downloaded as a whole, makes it more complicated (although not impossible) to replicate and redistribute it to peers. Simultaneously, it gives a high flexibility and mobility for the user since the access to one's favourite playlists can be reached from multiple locations and hardware. For instance, the company launched applications for iPhone and Android mobile systems in 2009 and for Windows Mobile in late 2010, offering users access to their playlists through their mobile phones.

In 2010, Spotify opened up new social dimensions to their music service, as they introduced a function where users can create a profile and publish their playlists of artists and tracks for public view. The profiles in themselves are not including much information and functionality, but by linking them to social websites, such as Face-book, Twitter and Messenger, opened a possibility of sharing music tracks and playlists with peers. Initially, Spotify did not have features for users to communicate directly with each other via the client program, but in April 2013 they released such function. Still, however, Spotify does not allow its users to be directly involved in the development of functionality or content.

Unlike TPB, the users or artists themselves are not allowed to upload any content to the catalogues. This can only be done through the contracts signed with the record label companies or other established artist aggregators. Hence, Spotify retains a tight control over the music content, ensuring that property rights are not being violated. In that sense, Spotify has similarities to iTunes who use Digital Rights Management (DRM) to enforce users to respect copyright laws. But Spotify's streaming technology gives the user instant access to a large music content without needing to download and pay for each song. Spotify have a so called 'freemium' business model, where a base functionality is free for the user (although with advertisements interrupting between tracks), while premium functionality is offered to paid subscribers (approximately 10 euro per month) in terms of commercial-free, higher bit rate streams, access through mobile phone, and offline access to music. According to the license agreements, a proportion of the income streams are handed over to the copyright owners. The major record companies also received shares in Spotify when contracts were signed. The founders, Ek and Lorentzon, have been vocal in the debate about the digital revolution and its effect on the music industry, highlighting that Spotify is a legal alternative to the pirates. In several newspaper interviews, Ek has said that 'Our point of departure is to generate a legal service which can compete directly with the pirate services'. Indeed they seek to brand their offering precisely in opposition to illegal pirates in their internal promotions on the site, to the extent that on the free service, declarations of their being an alternative to pirate sites are as frequent as the commercial adverts. This approach probably helped Spotify to pronounce itself as a Technology Pioneer in the World Economic Forum 2010 and the entrepreneurs behind the web service have several times been collecting entrepreneurship prizes and awards. For instance, Daniel Ek was named by Wired Magazine as the greatest digital influence in Europe in 2014. As of 2012, the CEO and founder Daniel Ek was ranked 395th on the British rich list with a calculated worth of £190 million.

However, voices have also been raised concerning the inadequacy of the licensing deals with the artists, arguing for a more transparent income process. For instance, in 2009, it was claimed that the superstar Lady Gaga received just $167 from Spotify for her hit 'Poker Face' during a five month period when the song was streamed over a million times. The company then insisted that the money would increase vastly as more subscribers enter and advertising revenues escalate. In 2014, the American country singer Taylor Swift also voiced her critique against Spotify and pulled out her whole catalogue of songs in protest of the size of royalties. Spotify answered in a blog post;

Quincy Jones posted on Facebook that 'Spotify is not the enemy; piracy is the enemy'. You know why? Two numbers: Zero and Two Billion. Piracy doesn't pay artists a penny - nothing, zilch, zero. Spotify has paid more than two billion dollars to labels, publishers and collecting societies for distribution to songwriters and recording artists. A billion dollars from the time we started Spotify in 2008 to last year and another billion dollars since then. (2014-11-11)

The 'disruptiveness' of TPB and Spotify and an actor network analysis

TPB and Spotify are to be considered as 'radical' music services in terms ofhow they have opened up new ways of providing music to the public, and in doing so have challenged the existing business structure in the industry. Both ventures have utilized new digital technologies as a vehicle for music distribution, but TPB and Spotify have different programs-of-actions inscribed in their 'radical' technologies, in line with the purpose of enrolling their different defined stakeholder groups. The technological designs are, thus, closely linked to how each initiative differentiates itself toward the incumbent firms, and how they are constructed to facilitate content and usage of content. This is what Callon (1986) calls interessement, i.e. the process of attracting selected parts of the environment to be mobilized into the venture.

For TPB, the end-users are considered the most relevant social group, and the interessement process is aimed at providing them a platform for sharing material in an easy, free, anonymous and effective way. For these users, the service provider has few restrictions as they do not censor any content or shut down any user accounts. TPB has instead chosen a highly distributed approach for uploading as well as downloading of content. The service is relying solely on user activities, and that is why it is important to involve the interest of the masses of active end-users. Due to its' nowadays millions of users' uploads, the website's search index includes a large variety of material - from the latest top hits to obscure bootlegs and private remixed versions. Of-ten, a huge number of tracks are zipped into one big file, e.g. a collection of albums from one specific artist, a music era or a genre, which escalates the downloading process further. The sound quality can of course also differ, the tag information can be diverted and files may be destroyed or, in a worst-case scenario, infected with a virus. However, since the users' ongoing file-sharing activities are disclosed together with members' comments, preferences and discriminations can guide the seeker to 'good' content in a self-organizing way.

Another potential stakeholder group for TPB is the intellectual property owners of content. In this case, TPB representatives did not put down effort to align the web service in accordance to this group's interests. The website has no compensation structures in place to pay artists, producers, distributers or any other copyright holders. The anti-programs from some of these actors have also been very outspoken as the dominant music industry actors both sue TPB in court and use public media to discredit the website as 'evil pirate'. From the rhetoric of the music industry and the media it is easy to get an impression that all of the material is illegal, but TPB hosts torrents directed toward both copyright- and non-copyright material and it can sometimes be difficult for the file-sharer to know which one is which. To answer the anti-programs of aggressive copyright owners, representatives of TPB earlier replied in a rather ironic and ridiculing language. This language war led to a positioning of the web service as an illegal copyright intruder, but also as a rebellious place for the young generation of music lovers. In fact, it could be argued that the design of the web service is enhancing resilience not only to an effective spread of digital content per se, but also to the shielding of file-sharers with illegal intentions; it is distributed to a large population which makes it difficult to trace and to sort out who is doing what, it is anonymous and accessible from any internet connection, and the interaction with the site is limited to the torrent downloading which is a very short time. The site's name and logo - indicating a calm bay for pirates - also supports this rather deliberate positioning in favour of piracy on almost ideological terms. Hence, the dissociation from the big record labels made them simultaneously one of the most important actants for mobilizing the website. The distributed users embraced to a large extent this 'pirate' position, and continued its 'mission' even after the initial founders were legally stopped by the court. Even for some property owners (predominantly smaller record labels and artists) TPB - with its radical image and effective distribution channels - was appreciated as a means to fight the dominant incumbents of the industry.

While sharing the same problematization of how to access music freely or at economic prices, Spotify differs from TPB both in the range of content it offers but also in the process of interessement through which it mobilizes parts of the environment. Rather than demonize the suppliers of its products, it has mobilized them, the law and advertisers as allies by which it can differentiate itself from those networks such as TPB that alienate suppliers by facilitating the breaching of copyright by users. Spotify has established a gatekeeping authority over the offered material, being an obligatory passage point (Callon, 1986) in deciding which tracks are allowed to be streamed by the users. This makes it possible to secure good sound quality and opens up possibilities to organize the content in a user-friendly way. Context information about the artist and the album can be imputed and changed whenever necessary and related music can be linked making it easy to find new favourites. In addition, because it is not illegal, Spotify is linked to other social media as means of enrolling and mobilizing additional users through its network of existing users. The established licensing agreements with record labels have formed a business model where copyright owners receive income from the activities on Spotify, and through the gatekeeping role it is possible to make sure that no illegal material is accessible. This also means that Spotify can remove access to a streamed track whenever they want, even if the users have bookmarked it in their playlists. The fact that Spotify has proprietary ownership of the technology allows them to support this strategy through Digital Rights Management (DRM) and to continuously upgrade and improve its functionality and copyright protection simultaneously.

Spotify has, hence, several parallel relevant social groups that they need continuously to enrol; (e.g. users, advertisers and content owners). Instead of opposing or ignoring intellectual property issues, the web service has rather utilized the copyright and DRM to accelerate their businesses although the business model operates on two distinct fronts - a free service with restrictions on users extending their network of use to non-internet connections or a subscription service that frees the user from these restrictions as well as from advertising interruptions. While funding the free service comes from advertising, this facilitates enrolment of users by giving them a basic service from which large numbers upgrade. The design of the music service facilitates, in terms of establishing control over content as well as technology, a positioning in direct opposition to the 'evil' pirates. By contrast, Spotify can claim to act as the noble knight who will rescue the confused music industry facing disruptive or destructive aspects of the digital revolution. While TPB can be seen as a service mainly delivering value to the file-sharers, Spotify is balancing the inclinations of various actors as well as mobilizing nonhuman actors in the network; copyright owners are protected from illegal file-sharing and receive new income streams, and users get a well-functioned, user friendly and accessible music service with a large up-to-date music catalogue within the confines of intellectual property.

The comparison between TPB and Spotify suggests that digital music services should not be lumped together into a homogeneous group since they differ on several key technological, organizational and intellectual property dimensions. These aspects are highly linked and congruent for TPB as well as for Spotify and their various combinations position them rather differently in relation to the industry incumbents and to the overall industry development as such. Put differently, their mobilized associations and dissociations to other social and technological elements make up the unique identity and direction of each venture.

From Christensen's (1997) argumentation on sustaining and disruptive innovations, TPB as a macro actor (Callon & Latour, 1981) shows many disruptive aspects. Due to its mobilization of millions of users and the hosting of about 5 million torrent files, TPB can speak with a disdainful or irreverent voice against the established power structures of the music industry. In this way it questions the view of consumers as passive content recipients and the business logic of paying for the carrier (e.g. cassette, LP, CD, DVD) of music. Continuing the journey that predecessors such as Napster and Kazaa started, TPB could be seen as having a transforming potential on the music industry and its enrolment process poses a threat to the big recording firms' oligopolistic structure in a vein not dissimilar to the independent labels' attempts in the 1950s. This is in line with the Schumpeterian (1934) view of entrepreneurship - as a function of creative destruction to the market, enforcing imbalances and opening up new opportunities. Actor network theory, however, provides a more detailed perception on how the creative destruction emerges in practice, as a translation and mobilization process of technical as well as social elements.

Spotify, on the other hand, has aimed to mobilize both the users and the intellectual property owners (including large incumbent music corporations) in parallel. This means a balancing of different proble-matization and interessement activities toward the two stakeholder groups. To users, the focus is put on quality, instant availability and user friendliness - above the fact that it is digital, free(mium) and legal. To content providers, the focus is put on being a new distribution channel to a large customer base through a service safe from illegal use and with a business model in place to protect the income streams of intellectual property owners. In this way, Spotify rather acts as a saviour to the music industry, supporting the big corporations in the war against pirates. And as legal music services such as Spotify are being incorporated into the income streams of large incumbent firms, peer-to-peer and streaming technologies are largely being transformed from a disruptive to a sustaining force.

Despite obvious differences in their associations with social and material elements, TPB and Spotify can be considered as having a symbiotic rather than conflicting relation. Although the Spotify founders speak loudly about pirates as a threat to the music industry, the existence of piracy is in fact one of the strongest door-openers for legal digital music services to be accepted by the dominant market actors. In effect, piracy provides Spotify with the conditions for generating their own legitimacy. Piracy is the unacceptable Other (Derrida, 1982) through which Spotify can secure its existence. In similar ways, TPB partly legitimizes itself as a revolt against the big corporations' power over the passive users. TPB and Spotify are in basic terms performing a similar service - i.e. providing music to a large population of music lovers utilizing 'radical' digital technology - but they have mobilized themselves differently in terms of rhetoric and associations to social and material elements. One of the actors is positioned as the biggest enemy of the established music industry and the other as the Entrepreneur of the year.

Streaming- and peer-to-peer technologies are arguably as radical to the music industry as the phonograph, the radio and the cassette tape recorder was earlier in history. But as the comparison between TPB and Spotify shows, it is not only the 'inner' features of the technologies that define their level of disruptiveness on the behaviours of users or the structure of the market. To an equal degree, it is the associations each venture has developed and maintained with respect to other elements, such as to the acceptance or rejection of the rights of dominant proprietary owners and to the discourses of piracy as good or evil, which energize its impact as a sustaining or disruptive inno-vation. The power of disruption is, hence, to be found in the music service's associations in actu, and will therefore always be up for grabs (Latour, 1986). Associations holding together a disruptive innovation could be strengthened or diminished, depending on how the various actors interact and intersect, but it is not only in the core technology that one will find the answer for what impact a certain initiative will have on the market, what direction it will move in, where it will be displaced. It is much more in the actor networks that are rendered more or less robust through complex relations within and between technological artefacts and socio-political associations.

Conclusion

Inspired by actor network theory, this article suggests an alternative framework for looking at disruptive innovations which challenge the mainstream approaches based on technology-centric and diffusion model-based assumptions. It agrees with previous critiques of the notion of disruption as non-precise and with limited predictive use (Dan & Chieh, 2010; Danneels, 2004; Markides, 2006; Tellis, 2006). What is or isn't a disruptive innovation has not been the main question for this article, but it is arguably important elsewhere to sort out the differences between disruption in terms of altered value proposi-tions, consumption patterns and/or market structures. Regardless of the definition and in contrast to the above critiques of ideas around disruption, however, we argue that the solution to the 'innovator's dilemma' (Christensen, 1997) is not to be found in a further examination of technological features and design, finer categories and classifications, and internal organizational structures and attitudes. Rather, one needs to thoroughly examine and describe the innovation in relation to its processes of establishing obligatory passage points around certain problematization and interests that enrol material and human actors around networks mobilized to a point where alternatives seem implausible or are denied. Hence, the disruptive power of innovation depends on how it succeeds in associating itself with certain cultural, political and social norms.

Determining the disruptive innovations through studying what is already-made rather than its development in the making (Latour, 1987) is rather unproblematic (although not necessarily useful), as all the associations then have been silenced and black-boxed (Callon & Latour, 1981). But we follow the proposition that innovations are travelling ideas (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996) in continual processes of becoming constituted through associations that they themselves constitute. Here there is no presumption of stability since actor networks can implode as readily as reproduce themselves (Latour, 1986), but it forces analysts as well as network members to move away from a preoccupation with technology per se, and instead to examine more carefully the technology's linkages with social and organizational content in the contexts of innovation management.

For practitioners, to highlight not only the material but also the social, does perhaps not solve the 'incumbent's curse' (Chandy & Tellis, 2000), but it would potentially release the decision makers' energy toward actively enrolling and mobilizing new associations rather than solely protecting the already stabilized ones. Furthermore, the focus on social, economic and technical interactions rather than mainly on technological features illuminates the highly difficult managerial challenge of predictingfuture disruptive threats, as these forms of 'association battles in the making' often lead to unpredictable outcomes and unforeseen consequences (Callon & Law, 1982). It also facilitates the understanding that a technology's potential for disruption resides as much with followers as with inscribers (Latour, 1987) - including the industry actors (i.e. producers), but more so the users (including 'pirating' music lovers).

References

Abbott, A. (1992). What do cases do? Some notes on activity in sociological analysis. In C. C. Ragin & H. S. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry (pp. 53-82). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Abernathy, W., & Clark, K. (1985). Innovation: Mapping the winds of creative destruction. Research Policy, 14(1), 3-22. [ Links ]

Ahuja, G., & Lampert, M. C. (2001). Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: A longitudinal study of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6-7), 521-543. [ Links ]

Akrich, M. (1992). The DeScription of Technical Objects. In W. E. Bijker & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change (pp. 205-224). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Ali, A. (1994). Pioneering versus incremental innovation: review and research propositions. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11(1), 46-61. [ Links ]

Anderson, P., & Tushman, M. (1990). Technological Discontinuities and Dominant Designs: A Cyclical Model of Technological Change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35 (4), 604-633. [ Links ]

Baym, N. (2010). Personal Connections in the Digital Age. Cambridge; Malden, MA: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Benkler, Y. (2006). The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Bower, J., & Christensen, C. (1995). Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave. Harvard Business Review, 73, 43-53. [ Links ]

Callon, M. (1986). Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, Action and Belief (pp. 196-233). London, Boston and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Callon, M. (1991). Techno-economic Networks and Irreversibility. In J. Law (Ed.), A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power, Technology and Domination (pp. 132-161). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Callon, M. (1992). The Dynamics Of Techno-Economic Networks. In R. Coombs, P. Saviotti & V. Walsh (Eds.), Technological Change and Company Strategy (pp. 72-102). San Diego: Academic Press Inc. [ Links ]

Callon, M. (2007). What does it Mean to Say That Economics Is Performative? In D. A. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa & L. Siu (Eds.), Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics (pp. 311–357). Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Callon, M., & Latour, B. (1981). Unscrewing the Big Leviathan or How to do Actors Macrostructure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them Do So. In K. Knorr & A. Cicourel (Eds.), Advances in Social Theory and Methodology: Toward an Integration of Micro and Macro Sociologies (pp. 277-303). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Callon, M., & Law, J. (1982). On Interest and Their Transformation: Enrolment and Counter-Enrolment. Social Studies of Science, 12(4), 615-625. [ Links ]

Chandy, R. K., & Tellis, G. J. (1998). Organizing for Radical Product Innovation: The Overlooked Role of Willingness to Canibalize. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(4), 474-487. [ Links ]

Chandy, R. K., & Tellis, G. J. (2000). The Incumbent's Curse? Incumbency, Size, and Radical Product Innovation. The Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 1-17. [ Links ]

Christensen, C. (1997). The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Christensen, C., & Raynor, M. (2003). The Innovator's Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Coombs, R., & Hull, R. (1998). 'Knowledge management practices' and path-dependency in innovation. Research Policy, 27(3), 239-256. [ Links ]

Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, B. (1996). Travels of Ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating Organizational Change (pp. 13-48). Berlin: de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Dan, Y., & Chieh, H. (2010). A Reflective Review of Disruptive Innovation Theory. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 435-452. [ Links ]

Danneels, E. (2004). Disruptive technology reconsidered: A critique and research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(4), 246-258. [ Links ]

Derrida, J. (1982). Margins of Philosophy. Chicago: Universithy of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Dewar, R., & Dutton, J. (1986). The adoption of radical and incremental innovations: an empirical analysis. Management Science, 32(11), 1422-1433. [ Links ]

Dosi, G. (1982). Technological paradigms and technological trajectories : A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Research Policy, 11(3), 147-162. [ Links ]

Duchêne, A., & Waelbroeck, P. (2006). The Legal and Technological Battle in the Music Industry: Information-Push versus Information- Pull Technologies. International Review of Law and Economics, 26(4), 565-580. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building Theory from Case Study Research. Academy of management Review, 14(4), 532-550. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K., & Graebner, M. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25-32. [ Links ]

Ettlie, J. E., Bridges, W. P., & O'keefe, R. D. (1984). Organization strategy and structural differences for radical versus incremental innovation. Management Science, 30(6), 682-695. [ Links ]

Farrell, J., & Saloner, G. (1985). Standardization, Compatibility, and Innovation. Rand Journal of Economics, 16(1), 70-83. [ Links ]

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study re search. Qualitative inquiry, 12(2), 219-245. [ Links ]

Foster, R. N. (1986). Innovation: The attacker's advantage. New York: McKinsey. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and other Writings 1972-77. London: Tavistock. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1982). The Subject and Power. In H. L. Dreyfus & P. Rabinow (Eds.), Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics (pp. 208-226). Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press. [ Links ]

Govindarajan, V., & Kopalle, P. (2006). The Usefulness of Measuring Disruptiveness of Innovations Ex Post in Making Ex Ante Predictions*. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(1), 12-18. [ Links ]

IFPI. (2014). Digital Music Report 2014. In. [ Links ]

Kleinschmidt, E. J., & Cooper, R. G. (1991). The impact of product innovativeness on performance. Journal of Product Innovation Mana gement, 8(4), 240-251. [ Links ]

Knights, D., Noble, F., Vurdubakis, T., & Willmott, H. (2002). Allegories of Creative Destruction: Technology and Organisation in Narratives of the e-Economy. In S. Woolgar (Ed.), Virtual Society? Technology, Cyberbole, Reality (pp. 99–114). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Knights, D., & Vurdubakis, T. (2005). Editorial: Information technology as organization/disorganization. Information and Organization, 15(3), 181-184. [ Links ]

Kuhn, T. S. (1965). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: Phoenix books. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (1986). The Powers of Association. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, Action and Belief (pp. 264-280). London, Boston and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (1987). Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (1996). Aramis or the Love of Technology. Cambridge; London: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction To Actor- Network-Theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lessig, L. (2004). Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity. New York: Penguin. [ Links ]

MacKenzie, D. A., & Wajcman, J. (1999). The Social Shaping of Technology. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Markides, C. (2006). Disruptive Innovation: In Need of Better Theory*. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(1), 19-25. [ Links ]

McDermott, C., & O'Connor, G. (2002). Managing radical innovation: an overview of emergent strategy issues. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 19(6), 424-438. [ Links ]

Orlikowski, W. J. (2007). Sociomaterial Practices: Exploring Technology at Work. Organization Studies, 28(9), 1435-1448. [ Links ]

Rennecker, J., & Godwin, L. (2005). Delays and interruptions: A self- perpetuating paradox of communication technology use. Information and Organization, 15(3), 247-266. [ Links ]

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press of Glencoe. [ Links ]

Sandström, C. (2011). High-end disruptive technologies with an inferior performance. International Journal of Technology Management, 56(2-4), 109-122. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry Into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Siggelkow, N. (2007). Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 20-24. [ Links ]

Solow, R. M. (1957). Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 39(3), 312-320. [ Links ]

Stake, R. (2000). Case Studies. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (Vol. 2, pp. 435-454). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), 285-305. [ Links ]

Tellis, G. J. (2006). Disruptive Technology or Visionary Leadership? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(1), 34-38. [ Links ]

Tushman, M. L., & Anderson, P. (1986). Technological Discontinuities and Organizational Environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31(1), 439-465. [ Links ]

Utterback, J. M. (1994). Mastering the dynamics of innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Yin, R. (1994). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Vol. 5). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Submitted: May 27th 2016 / Approved: September 11th 2016